For the next few days, I’ll be posting excerpts from Nancy Guthrie’s Jesus, Keep Me Near the Cross: Experiencing the Passion and Power of Easter (Crossway). Join me as I aim to contemplate the cross this passion week.

For the next few days, I’ll be posting excerpts from Nancy Guthrie’s Jesus, Keep Me Near the Cross: Experiencing the Passion and Power of Easter (Crossway). Join me as I aim to contemplate the cross this passion week.

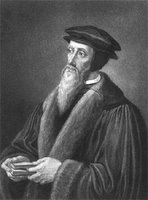

Today’s meditation is by John Calvin, from chapter 17 “Blood and Water” (pg. 103-104 of Jesus, Keep Me Near the Cross, edited by Nancy Guthrie).

“Not one of his bones will be broken.” This quotation is taken from Exodus 12:46 and Numbers 9:12, where Moses refers to the paschal lamb. John takes it for granted that that lamb was a figure of the true and only sacrifice through which the church was to be redeemed. This is consistent with the fact that it was sacrificed as the memorial of a redemption which had been already made. As God intended it to celebrate the former favor, he also intended that it should show the spiritual deliverance of the church, which was still in the future. So Paul without any hesitation applies to Christ the rule which Moses lays down about eating the lamb: “For Christ, our Passover lamb, has been sacrificed. Therefore let us keep the Festival, not with the old yeast, the yeast of malice and wickedness, but with bread without yeast, the bread of sincerity and truth” (1 Cor. 5:7-8).

From this analogy, or similarity, faith derives great benefit, since in all the ceremonies of the law it views the salvation which has been displayed in Christ. This is the purpose of the evangelist John when he says that Christ was not only the pledge of our redemption but also its price in that we see accomplished in him what was formerly seen by the ancient people under the figure of the Passover. In this way the Jews are also reminded that they ought to seek in Christ the substance of everything that the law prefigured but did not actually accomplish.

Christ truly is our Passover Lamb. A deliverance greater than that of the Jews from the bondage of Egypt (and the fury of the Death Angel) was effected by His death. Christ is without blemish, and his bones were not broken. He was brutally sacrificed for us, in our place. May His sacrifice for our sins grip us to the extent that like a Jewish home in Goshen, Jesus’ blood would adorn the door posts of our hearts. May we glory in nothing else but His Cross.

Loved by many, yet hated by more. John Calvin, the great Reformer, has bequeathed us a schizophrenic legacy.

Loved by many, yet hated by more. John Calvin, the great Reformer, has bequeathed us a schizophrenic legacy.